INTRODUCTION

The nose is highly contoured and occupies a central position on the face. These characteristics allow small asymmetries and imperfections of the contour to be easily noticeable [

1]. The nose is also functionally important, as it plays crucial roles in breathing, olfaction, and phonation and is structurally complex. Therefore, nasal reconstruction is a highly challenging surgical procedure.

Complete reconstruction of the nose requires reconstruction of the inner mucosal lining, external nostril lining, and supporting structures [

2]. The method of reconstruction should be chosen from the numerous options available based on the patientŌĆÖs needs, the goals of reconstruction, the specific location, and the surgeonŌĆÖs skill with a particular technique [

3]. Reconstruction of partial-thickness alar defects can be performed with a simple primary closure or a local flap, but large full-thickness defects require a more complex method, such as a forehead flap or free flap. The subcutaneous pedicled nasolabial flap has been used as a reconstruction method for large full-thickness alar defects. Herbert [

4] showed that even a large flap can survive with a narrow subcutaneous pedicle due to the abundant vascular distribution of the nasolabial skin. However, this is a two-stage procedure, which causes significant patient trauma, is laborious for the surgeon, results in proportionate surgical risk, and imposes a substantial financial burden. These limitations highlight the need for improved options. Herein, we introduce a folded nasolabial island flap (FNIF), which is a modification of the nasolabial flap. The FNIF retains all the benefits of a nasolabial flap and addresses its limitations. FNIF can be used to reconstruct alar defects without cartilage graft (a common requirement in nasolabial flaps), allows adequate maintenance of the external nasal valve, and is less time-consuming.

RESULTS

The age of the patients ranged from 51 to 82 years (mean, 65.6 years). Five patients were male, and two were female. Five patients were smokers. Six patients had been diagnosed with skin cancer (basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma), and one patient had trigeminal trophic syndrome after herpes zoster infection. All operations were performed under general anesthesia. For oncologic surveillance, all patients received a split-thickness skin graft during the first operation, which was removed during the following flap operation. The mean flap size was 2.6 ├Ś 6.6 cm. No complications occurred (

Table 1).

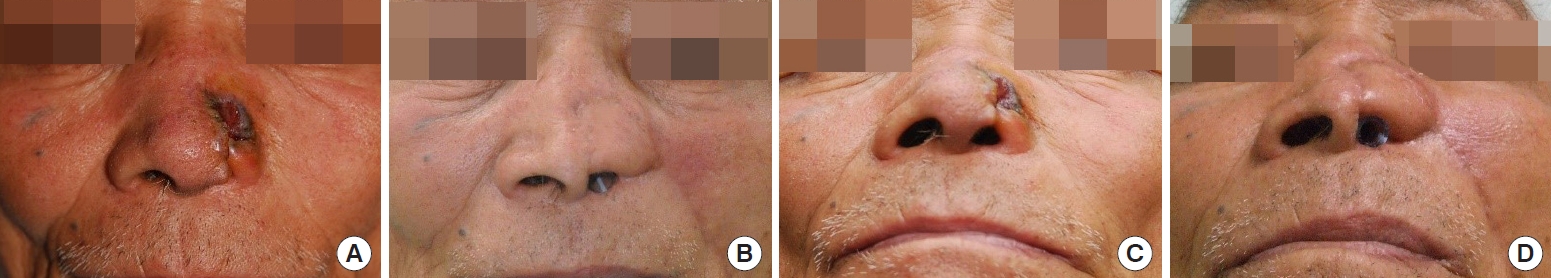

The flap was then monitored and cleaned daily. One week after the operation, the flap was fully viable without minor wound complications, such as flap congestion or infection. The alar rim was slightly thicker than ideal in the wormŌĆÖs view, but there were no functional problems, and the airway patency was well maintained.

Three months after surgery and flap maturation, the inserted tube was removed. The nostril lining did not collapse, and there was no hypertrophic scarring. The nasolabial fold of the flap elevation site was faint compared to that on the contralateral side, but the fold line was visible. Air movement through the nostrils on the flap side was comfortable and unobstructed, as was the case on the contralateral side. Patients did not experience discomfort during inhalation or expiration. All patients were satisfied with the functional and aesthetic results of the operation (

Figs. 2-

4). Based on the appearance of the patients before and after the operation, other physicians determined the aesthetic outcomes to be ŌĆ£very goodŌĆØ or ŌĆ£excellentŌĆØ (

Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Reconstruction of alar defects is challenging due to the single-subunit structure of the ala and its limited mobility [

6]. Causes of nasal defects include traumatic injury, viral infections, and tumor resection [

7]. A wide range of reconstruction methods for alar defects can be chosen according to the size and depth of the defect, including primary repair, skin graft, composite auricular graft, cheek advancement, septal mucosal flap, and paramedian forehead flap. However, there are limited flap options for full-thickness alar defects.

The septal mucoperichondrial flap and forehead flap are suitable reconstructive options for full-thickness alar defects; however, they are technically challenging [

1]. The septal mucoperichondrial flap is an example of a lining flap, and a thinner lining of the nostril can be expected with this technique than with other local flaps. However, it requires skilled techniques and a steep learning curve, and it is difficult to accurately predict the symmetry and surgical outcomes. The median forehead flap is widely used to reconstruct defects in all nose subunits with a wide range of sizes [

8]. However, the most substantial drawback of this flap is the donor site scar that forms in the central forehead area, especially in Asian populations [

9]. Unlike Caucasians, the nose of Asians generally has a flat, wide base of the bony pyramid, less muscle volume, and a flatter glabella [

10]. Most importantly, Asians have thicker skin than Caucasians, and scars are more pronounced when forehead flaps are made [

11]. The maximum possible width of the donor site of the median forehead flap is approximately 4 cm, but if the width is more than 2 cm, it is considered aesthetically unsatisfactory [

12]. Nasolabial flaps are generally less preferable for Caucasian men due to the dense beard and differences in skin texture.

The ear cartilage graft is often used to prevent the collapse of the nostril lining; by doing so, alar defects can be easily reconstructed using a two-layer composite graft [

13,

14]. A cartilage graft is also used to achieve normal airway patency and appropriate contours [

1]. However, in a retrospective analysis of 13 patients who underwent free cartilage graft, van der Eerden et al. [

15] reported unsatisfactory aesthetic outcomes in 23% of cases. Cartilage grafts also have a risk of infection (i.e., chondritis) and discoloration. Therefore, satisfactory results cannot be achieved using cartilage composite grafts.

The Spear flap is an excellent, aesthetically impressive, one-step reconstructive method for full-thickness lateral alar defects with a ŌĆ£turn overŌĆØ nasolabial flap. It hides the flap donor site scars within the nasolabial folds. In addition, the flap pedicle can be preserved at the alar base, and the proximal half of the flap can be used for the internal mucosal lining, while the distal half can be used for nostril lining [

16]. It is initially sutured from the alar base to the columella to form a mucosal lining and then folded to form an appropriate outer nostril lining. The framework of the folded flap is satisfactory; therefore, no cartilage graft is required [

5]. However, it may not be a good option for Asians, who have thicker skin than Caucasians, as it can induce severe asymmetry. A sliding flap similar to the nasolabial flap is based on the anterior superior subcutaneous pedicle. The superomedial portion of the flap was used to make the outer nostril lining, and the lower portion was partially defatted and inset at the site of the alar defect [

17]. The Spear flap generally requires flap revision, such as flap thinning and medial shift of the alar base after the flap has stabilized [

2].

Yoon et al. [

18] described facial artery perforator-based nasolabial island flaps for the reconstruction of perinasal defects. In that study, defects on the nasal dorsum, columella, and ala were reconstructed using nasolabial flaps with 120┬░ŌłÆ180┬░ rotation. Our study is different from the study by Yoon et al. in that we only included patients with full-thickness skin defects. Our method can cover the inner mucosal lining by folding the distal end of the nasolabial flap to prevent the collapse of the nostril.

Taken together, our FNIF method has several advantages. First, in patients with full-thickness defects, the complex structures of the inner mucosal defect, architectural support, and outer nostril lining are reconstructed at once rather than in two stages. As a result, patients can avoid unnecessary additional operations, thus reducing morbidity and medical costs. Furthermore, it is also possible to correct the airway patency problems and asymmetry that appear in the existing transposition flap by promptly performing an appropriate debulking procedure immediately after flap inset, rather than later during postoperative follow-up. Because this folding flap is composed of two layers containing the dermis and subcutaneous fat, it maintains desirable stiffness and is structurally stable. Second, the FNIF is technically easier to perform than many existing reconstruction approaches for large and complex alar defects. The folding position of the FNIF can be freely adjusted according to the size of the alar defect and the projection of the tip. Third, a composite cartilage graft is unnecessary for the FNIF because the structure and convex shape of the lateral ala remain stable for a long period postoperatively without cartilage. Finally, FNIF preserves the sensory nerve, unlike the two stage flap methods, which cause sensory loss.

In this study, there were no complications, such as infection or flap congestion. Blood flow around the ala was abundant, and there were numerous subcutaneous perforators. Therefore, the flap perfusion was adequate, and the chances of flap survival were high.

However, the FNIF described herein has several disadvantages. First, the newly reconstructed ala remained unnaturally thick for a long period and showed asymmetry as the alar base moved laterally. However, if asymmetry causes discomfort, the alar base can be medialized using a small Z-plasty or transposition flap. This is because the folding flap has been reconstructed to be sturdy and thick to maintain the proper strength of the nostril lining. Second, the tubing should be maintained in a specific location for more than 1 month to maintain the size of the nostril after reconstruction. Finally, our technique causes a loss of fat volume of the nasolabial fold corresponding to the amount of tissue used in flap elevation, resulting in asymmetry of the cheeks. Therefore, if possible, the scar should be positioned to align with the nasolabial fold, and the flaps should not be elevated with excess fat. Favorable aesthetic results can be achieved in donor site closure by forming a depressed scar through intentional suture inversion and creating an appropriate nasolabial fold.

This study has some limitations. First, it included a small number of patients, making it impossible to perform statistical analysis. Various surgical methods to cover alar defects have been discussed above, but surgical outcomes have not been compared with those obtained using other methods. Further studies are warranted to address these limitations.

The FNIF is different from the conventional nasolabial flap in that the FNIF is folded and twisted to achieve nostril reconstruction with a mucosal lining in three dimensions in one stage. The alar base can be successfully reconstructed using the FNIF, providing excellent aesthetic results and preserving nasal airway function. Despite the shortcomings mentioned above, our study demonstrates that FNIF is an effective, simple, and easy reconstruction method for large full-thickness alar defects.